Singlism and the pressure of being single

- READING TIME 11 MIN

- PUBLISHED March 12, 2024

- AUTHOR Donna

Key takeaways

- Singlism, the discrimination against single individuals, takes various forms, including social, economic, and institutional biases, persisting despite the prevalence of single-person households.

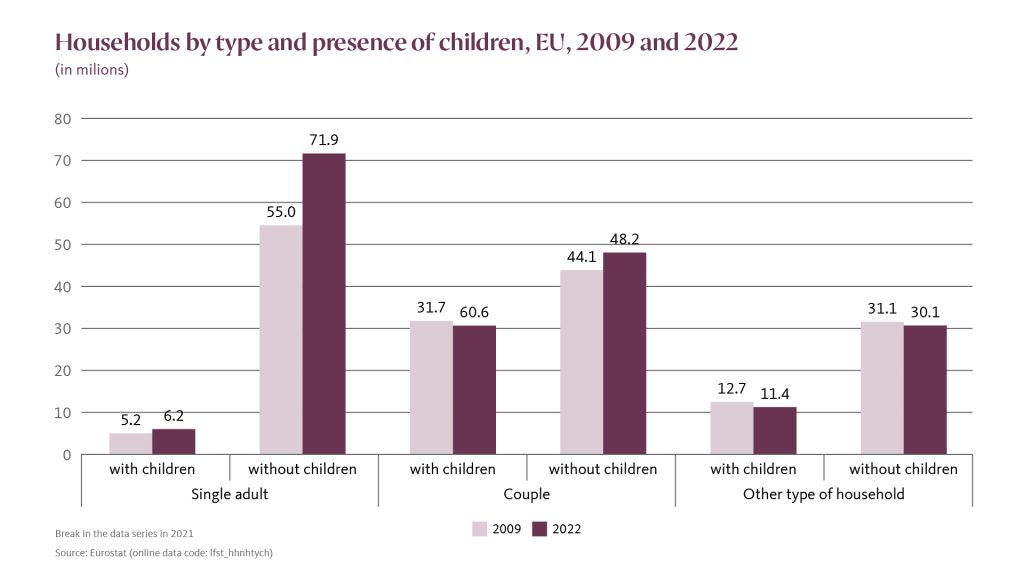

- In 2022, there were 71.9 million single adult households without children in the EU, constituting around 36% of all households.

- Being single promotes personal growth, strong social networks, better health, autonomy, and prepares individuals for future relationships, challenging societal stereotypes.

- We should encourage open-ended questions to dismantle the stigma of singlehood, fostering understanding and embracing the complexity of individual experiences.

Singlism and the pressure of being single:

How to end the hard time you’re getting from your coupled friends and family

Most of the people are single at one point in their life and many of us are probably familiar with the questions like “Why are you still single? When are you going to settle down?” or phrases such as “Don’t worry, you’ll find someone soon.” These phrases are much more common with unmarried women, and they tend to increase the older we get. But did you ever consider that being single isn’t something tragic or selfish, but it can also be a choice? The purpose of this article is to talk about the stigma of being single and to highlight the possible benefits of being single – to be better equipped with the knowledge and latest research. Either to understand the topic better or to help you win the arguments next time you’ll be faced with annoying questions regarding your relationship status.

Single without children: The most numerous household type the EU

More people than ever before are living single and without children – in 2022, the most numerous type of household in the EU were single adult households without children, amounting to 71.9 million, which is approx. 36% of all households.

It almost looks like being single is already normalized, doesn’t it? The data says otherwise – different studies report that almost half of unmarried women and one third of unmarried men report their coupled friends, family and co-workers giving them a hard time about their relationship status. While the pressure widely depends on location, sex and age, we need to start recognizing it exists – and it’s called singlism.

What is singlism?

Singlism is a term that refers to the negative stereotyping and discrimination against single people. This concept encompasses a wide range of biases and unfair treatment toward single individuals, and it can come in various forms:

- Social, cultural and psychological: Single people may be stereotyped as lonely, selfish, immature or unhappy. Social events and media often prioritize romantic relationships, which may make singles feel marginalized or excluded. The constant societal messaging that equates being in a relationship with happiness and success can affect mental health and self-esteem.

- Economic discrimination: Singles might face economic disadvantages like differences in tax policies, insurance rates and housing. Married couples can receive benefits and discounts that single people do not.

- Legal and institutional biases: Legal systems in many countries favour married couples in areas such as inheritance rights, spousal benefits and legal decision-making. Singles may not have the same rights to make medical decisions for incapacitated loved ones.

- Workplace: In some cases, single people might be expected to work longer hours or be more flexible with their time because they are perceived as having fewer personal commitments than their married counterparts.

- Healthcare: Singles can face disadvantages in terms of insurance and access to family-based health benefits. Policies are often designed with families in mind, which can leave singles paying more for less comprehensive coverage.

Despite the growing prevalence of single-person households without children, which now represent a significant portion of society, the issue of singlism persists, often overlooked or unrecognized as a form of discrimination that continues to affect many individuals’ daily lives. DePaulo (2022)1 shows that almost 40% of people don’t even recognize that singlism exists or then even deny it – even when participants were informed of examples in which single people were disadvantaged relative to coupled people.

The harms of single shaming

It can often happen that even small and not meaningful phrases can have a big effect on the psychological well-being of an individual. Phases such as “You’ll find someone soon” or “You must be so lonely” can deepen the stigma of singlehood. These stereotypes often include the idea that people in relationships have something more, a skill that singles are missing, or they include the idea that being single is tragic or even selfish.

These stereotypes aren’t just wrong, but they can have negative consequences because they affect the internalizing of the shame from a social point of view and can negatively affect self-image. Society expects us to “live by the book” – find someone, get married and have children – and when an individual is not following these “predefined” milestones, they can feel like they’re doing something wrong or even that something is wrong with them. A social script can even affect those who are happily single to seek a relationship, just because society expects them to.

For example, a study from Spielmann and colleagues (2013)2 showed that women who were afraid of being single are settling for less in the relationships. This means they are less selective while seeking a partner, which can result in a less successful relationship, or even that they tend to stay in an unhappy relationship due to their fear. Wouldn’t it be great if we, as a society, could help normalize the singlehood and offer stigma-free support instead of perpetuating the stereotypes?

Do you want to be single? Possible key to separating the advantages vs. disadvantages of being single

A lot of studies were made on the topic of singlehood, but they mostly focus on reasons for being single or the implications of being single – not a lot of studies were made about singlehood itself (Kislev, 2023).3 In general, many studies show incoherent results connected with singlehood, but as Kislev states, the missing link can be the relationship desire – when comparing those with low or high relationship desire, completely different research outcomes appear, including sociability, sex frequency, work-life balance and life satisfaction.

So, if we assume you’re happy with the choice of being single – what are the benefits?

- Personal growth and mental health. Research has shown that single individuals may have more opportunities for personal growth and development which can contribute to their mental well-being. Single individuals tend to invest more in their own development and they might be more self-sufficient (DePaulo, 2010).4 Personal development can come from the freedom to pursue one’s own interest and goals and the opportunity to learn how to cope with solitude, and they often engage in activities connected to self-discovery and personal achievement (Beckmeyer & Jamison, 2022).5 A recent study (Match, 2023)6 showed that singles are more focused than ever on self-betterment for the sake of themselves — and their future relationships. Young singles (Gen Z and Millennials) are the most proactive group: 45% worked on their mental health over the last year. This resulted in a promising increase in singles’ mental health.

- Stronger social networks. Studies (Chopik, 2017, DePaulo, 2017, Sarkisian & Gerstel, 2016)789 suggest that single people are more likely to maintain strong social networks and offer help to friends, family and neighbours. They often have the time and energy to nurture these relationships, which can lead to a robust support system. Several other studies showed also that single people have more friends and single people do more to maintain their relationships with friends, relatives, neighbours and co-workers. On top of that, singles get more psychological and emotional fulfilment from their friends and family (DePaulo, 2017, Burton-Chellew, Dunbar, 2015).810 These networks provide emotional support, avenues for social engagement and resources that can help with various life tasks, all of which can contribute to one’s mental health and sense of community belonging.

- Physical fitness and better sleep. Some studies (Match, 2023)11 indicate that single individuals tend to be more physically active, 48% of all singles worked hard to improve their physical health. They may have more time to devote to exercise and maintaining a healthy lifestyle, which can have long-term health benefits. Being single also affects sleep quality – without the need to accommodate a partner’s sleep schedule or habits, single people often report better sleep quality. Good sleep is linked to various positive health outcomes, including reduced stress and better mental health.

4. Freedom and autonomy. Embracing singlehood often comes with a high level of independence and self-governance. Without the need to compromise and coordinate with a partner, single individuals frequently experience a greater sense of freedom. This autonomy allows them to make life decisions – such as career moves, travel or personal hobbies – solely based on their desires and timelines (Berg-Cross, 2010).12 Studies have also indicated that singles appreciate the ability to control their own finances, time and living space (Apostolou & Christoforou, 2022)13, which can lead to greater life satisfaction and reduced anxiety about meeting societal expectations or managing relationship dynamics.

5. Being better prepared for possible future relationships. The experiences gained while being single can lay a solid foundation for healthier future partnerships. Single individuals often develop a strong sense of self-awareness and clear personal boundaries, which are essential for mutual respect in any relationship (Simon & Barrett, 2010).14 Research by Match (2023)15 has underscored that singles who have spent time reflecting on their own values and needs are more likely to enter future relationships with a clearer understanding of what they seek in a partner, leading to more meaningful connections. Additionally, singles tend to have developed effective communication skills and trust in their own judgment, making them well-equipped to build relationships based on trust, effective dialogue and mutual respect – the pillars that are central to lasting partnerships (Kislev, 2019).16

6. Bonus argument: I bet you didn’t expect the sixth argument! A recent study (van den Berg & Verbakel, 2023)17 revealed another function of singlehood in young adulthood – it may have a developmental function over the life course, buffering some of the negative effects of separation. The singlehood might help people build up certain skills that help them cope with the crisis effect of separation and they might have built more individual resources during the period that they were single – they may have invested more time in their own career and social networks. They might also be more confident in their abilities to be single because they’ve already had experience living on their own. In this way singlehood can prepare individuals to cope better with the possible separation that happens in later stages of life.

While singlehood can provide freedom and opportunities for personal growth, it’s not always a chosen lifestyle. Studies, such as those by Kislev, reveal that when individuals are single against their wishes, they may experience negative consequences like loneliness and reduced life satisfaction. The desire for a partner, when unmet, can affect one’s mental health, leading to increased stress and diminished social interaction. Ultimately, as we can see, the impact of singlehood varies greatly based on personal desires and societal influences. As with most of things, it all starts within us and how we perceive singlehood.

What can we do as a society against singlism?

Singlism, the discrimination against single people, is fundamentally flawed because it fails to recognize the complexity of singlehood. It fuels a one-dimensional view of singles, ignoring their diverse experiences and the reasons behind their marital status. It’s crucial that we, as a society, reevaluate our biases and our pressure on single individuals.

When faced with singlism from friends or family, who may unknowingly propagate this bias, it’s important to engage in constructive conversations. Hopefully, you can use some of the mentioned arguments to gently challenge their views, sharing insights about the benefits and challenges of single life, and the importance of respecting individual choices. Educating those around us can start with sharing personal stories or findings from studies that illuminate the subjective nature of singlehood, fostering empathy and broader perspectives.

Rather than imposing our preconceptions, we should offer support and understanding. Instead of posing the simplistic and often judgmental query “Why are you still single?”, we might ask “What’s something you’ve discovered about yourself during your time as a single?” This shift in dialogue honours personal journeys and fosters meaningful interaction, and challenges the stigma of singlehood. Isn’t it time we moved beyond outdated stereotypes and embraced the complexity of human experiences?

REFERENCES

- DePaulo, B. M., & Morris, W. L. (2006). The unrecognized stereotyping and discrimination against singles. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 251-254.

- Spielmann, S. S., MacDonald, G., Maxwell, J. A., Joel, S., Peragine, D., Muise, A., & Impett, E. A. (2013). Settling for less out of fear of being single. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 1049-1073.

- Kislev, E. (2023) Singlehood as an identity, European Review of Social Psychology, DOI: 10.1080/10463283.2023.2241937

- DePaulo, B. (2017). Toward a positive psychology of single life (pp. 251-275). In D. Dunn (Ed.), Positive psychology: Established and emerging issues. New York: Routledge.

- Beckmeyer, J. J., & Jamison, T. B. (2022). Empowering, pragmatic, or disappointing: Appraisals of singlehood during emerging and established adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 21676968221099124, 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968221099123

- Apostolou, M., Alexopoulos, S., & Christoforou, C. (2023). The price of being single: An explorative study of the disadvantages of singlehood. Personality and Individual Differences, 208, 112208.

- Chopik, W.J. (2017), Associations among relational values, support, health, and well-being across the adult lifespan. Pers Relationship, 24: 408-422. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12187

- DePaulo, B. (2017). Toward a positive psychology of single life (pp. 251-275). In D. Dunn (Ed.), Positive psychology: Established and emerging issues. New York: Routledge.

- Sarkisian, N., & Gerstel, N. (2016). Does singlehood isolate or integrate? Examining the link between marital status and ties to kin, friends, and neighbors. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(3), 361-384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407515597564

- Burton-Chellew, M. N., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2015). Romance and reproduction are socially costly. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 9, 229-241.

- Apostolou, M., Alexopoulos, S., & Christoforou, C. (2023). The price of being single: An explorative study of the disadvantages of singlehood. Personality and Individual Differences, 208, 112208.

- Apostolou, M., & Christoforou, C. (2022). What makes single life attractive: An explorative examination of the advantages of singlehood. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 8(4), 403–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-022-00340-1

- Apostolou, M., & Christoforou, C. (2022). What makes single life attractive: An explorative examination of the advantages of singlehood. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 8(4), 403–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-022-00340-1

- Simon, R. W., & Barrett, A. E. (2010). Nonmarital romantic relationships and mental health in early adulthood: Does the association differ for women and men? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(2), 168–182. DOI:10.1177/0022146510372343.

- Apostolou, M., Alexopoulos, S., & Christoforou, C. (2023). The price of being single: An explorative study of the disadvantages of singlehood. Personality and Individual Differences, 208, 112208.

- Kislev, E. (2023) Singlehood as an identity, European Review of Social Psychology, DOI: 10.1080/10463283.2023.2241937

- van den Berg, L., & Verbakel, E. (2023). The link between singlehood in young adulthood and effects of romantic separation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12954

RELATED ARTICLES

Explore more

Feed your curiosity with more content. Dive deeper and explore our selected articles, curated just for you.